Rob Calder and Dr Karen Bailey discuss the overlap between trauma and substance use problems, and how treatment services can adopt a trauma-informed approach to working with clients, without necessarily being experts in trauma. [The SSA’s Natalie Davies really wanted to be there but couldn’t make the meeting…so she wrote the questions.]

SSA: Can you tell us what trauma is, and why it’s important to incorporate a response to trauma within drug and alcohol services, particularly when providing treatment and support to women?

Dr Bailey: “I guess in the widest sense, trauma is an event or a series of events or circumstances that affects someone’s functioning and emotional, spiritual, and psychological wellbeing. In terms of diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), it’s a lot more specific – it includes having experienced actual or threatened death, actual or threatened injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence. And you have to have either been exposed to it, witness to it, or a professional on the front line that is repeatedly witnessing or being told horrific stories about those things.”

“A lot of people can develop symptoms from their experience of trauma. This can include: reliving the trauma as if it was happening in the here and now; being hyper-vigilant and hyper-alert; feeling irritable, jumpy, on edge, having sleep problems; and feeling negative emotions, including poor self-esteem, and depressive symptoms.”

It’s going to be really hard to address substance use problems without addressing trauma symptoms and behaviours.

“My area of interest is interpersonal trauma caused by domestic violence, sexual abuse, rape and childhood abuse. These types of trauma tend to have additional complications and symptoms. You hear people talk about ‘complex PTSD’. That often comes from interpersonal violence, and cumulative trauma either in childhood or adulthood, and can play out through problems with emotional regulation, the ability to relate to others, disturbances in personal relationships, and radically altered belief systems. For example, the belief that the world is inherently unsafe, the belief that you are inherently a bad person, a lot of self-loathing.”

“It’s going to be really hard to address substance use problems without addressing trauma symptoms and behaviours. And we’re particularly talking about women, who are over-represented as victims of domestic violence and sexual violence. If you don’t address the underlying symptoms, you’re not really going to be able to help someone to stop using drugs in a harmful way or self-medicating with substances to manage their symptoms.”

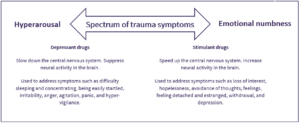

“In the past, I was involved with AVA’s Stella Project, which aimed to improve services for women affected by overlapping domestic violence and substance use problems. We used to refer to an image (see image below adapted for use on the SSA website) that plotted the spectrum of trauma symptoms and then the different substances that people might take to self-medicate.”

Copyright AVA 2016

“For example, someone who’s irritable or hyper-vigilant might want to take benzodiazepines or opiates to dampen those feelings down, whereas someone who’s not feeling anything or feeling numb or depressed might want to take something more stimulant-based to get themselves out of that.”

In your 2019 paper you explored practitioners’ experiences of supporting women with substance use problems, histories of abuse and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Their work arguably represented the best case scenario; it was closely aligned with ‘trauma-informed practice’. Can you tell us what this approach entails?

“Trauma-informed practice starts from an acknowledgement or assumption that interpersonal abuse is widespread in the substance use treatment population. It’s a framework or response at an organisational level that aims to avoid re-traumatisation and promote physical, emotional, and psychological safety. That’s what it is at the core. It doesn’t require the person to disclose their trauma. In its basic form, it actually doesn’t require a service to be screening or asking about violence or abuse. It’s the assumption that most people coming through that door of the service will have experienced trauma and ensuring that the service doesn’t re-traumatise.”

“Trauma-informed practice is also strength-based – it’s working on people’s strengths, capabilities, resilience, and building coping skills. Helping people to deal with being triggered by a smell or having a flashback. It’s giving people coping skills – often body based – something to smell (e.g. an essential oil on a scarf), calm them down, something nice to touch, breathing exercises. Quite simple things that you could put in place if someone is distressed in a treatment service.

In your paper you talked about practitioners’ work to ‘put out the fire’. I believe the full quote was “We have to put the fire out first before we start rebuilding the house”. Can you talk about why this metaphor resonated with the work practitioners were trying to do?

“I loved that quote. It was from one of the psychologists I interviewed who works with victims of domestic violence, and they were referring to the need to make people feel safe in treatment before doing anything else. This means making sure the person is physically safe in the service – for example, safe from an abusive partner or a pimp or other service users. It also means putting measures in place to build a sense of internal safety, which is giving people the coping skills to be able to manage their emotional responses (the skill of ‘emotional regulation’) and their flashbacks.”

“I interviewed a wide range of people – psychologists, domestic violence workers, substance use workers, professionals from the voluntary sector, NHS, and prison service. They didn’t use the same language, but they all essentially supported a staged or phase-based PTSD treatment model, which is the accepted model for PTSD that you see in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. The first stage is ‘safety and stabilisation’. Practitioners who weren’t necessarily trained to do the clinical PTSD work were focusing on doing this safety and stabilisation work to help women keep their emotions within a ‘window of tolerance’ (i.e. at a level where they could manage and cope with their emotions).”

All staff should have training in trauma awareness, including a basic understanding of the neurobiology of trauma.

“Until someone can regulate their emotions, they can’t really do the trauma processing. The next stage is the ‘rebuilding the house’ aspect, which is the stage of trauma processing. Some substance use services will offer it if they have a psychologist, but unfortunately nowadays that is rare.”

One final question. What do you think it will take for us to see integrated support for trauma and substance use problems extended across the UK?

“All staff should have training in trauma awareness, including a basic understanding of the neurobiology of trauma. For example, a particular smell might trigger a flashback for someone, and this response comes from the older mammalian part of brain that detects threats and is quicker than our executive functioning that makes judgements and decides on appropriate responses. The person may not understand this, but the member of staff should. They also need to understand that the behaviours of other people in the treatment centre or staff might be triggering as well. It might spark a memory of an abuser. Staff need to understand that – to see that being played out and then to act accordingly.”

“I definitely also recommend reading a book called The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, by Bessel van der Kolk. It really transformed my understanding of trauma and how to respond, particularly using body-based therapies.”

Karen Bailey is currently Associate Director for Patient Centred Outcomes at OPEN Health.

The opinions expressed in this post reflect the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official positions of the SSA.

The SSA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of the information in external sources or links and accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of such information.