Heroin uncertainties: Exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted ‘heroin’

Daniel Ciccarone, Jeff Ondocsin, Sarah G. Mars (2017) International Journal of Drug Policy 46, 146–155

In the September Qualitative Methods Journal Club members discussed the above titled paper which was published in the International Journal of Drug Policy in a Special Issue on US Heroin in Transition. The paper explored heroin users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated or fentanyl-substituted heroin. We were joined by Rebecca McDonald, who has recently completed her PhD examining naloxone, the antidote used for reversing opiate overdose. our discussions highlighted many strengths of the paper:

Overall, as researchers with a range of backgrounds and from a variety of disciplines, we found the paper very accessible and easy to read.

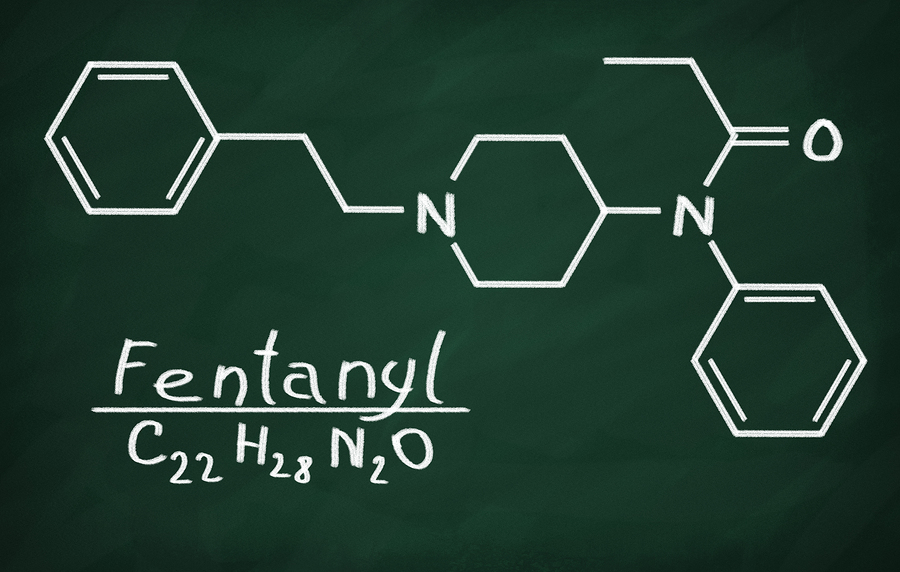

In the introduction, the authors convincingly position the scale of the issue – they provide very clear information regarding what fentanyl is, and the health risks associated with the use of opiates by way of the number of overdose deaths associated with heroin and more recently, fentanyl. They also provide a good overview of the regional patterns of fentanyl use in the US – particularly helpful for non-US readers, in line with the journal’s international scope and readership.

In the introduction, the authors convincingly position the scale of the issue – they provide very clear information regarding what fentanyl is, and the health risks associated with the use of opiates by way of the number of overdose deaths associated with heroin and more recently, fentanyl. They also provide a good overview of the regional patterns of fentanyl use in the US – particularly helpful for non-US readers, in line with the journal’s international scope and readership.

The authors also present a number of unknown areas, given the quickly changing situation and the limited existing research on the topic. The aim of the paper is clearly stated, along with some exploratory research questions. We liked how the authors justify the use of qualitative research to explore these unknown areas and questions.

The rapid ethnographic approach is explained at the start of the methods. Members unfamiliar with this approach welcomed this explanation and commented on the benefit of using the approach to obtain detailed data in a very short space of time – over a one-month period. The methods also provide clear detail on the study setting, recruitment strategies (via harm reduction workers and snowball sampling), eligibility criteria, who collected and analysed data, attempts to maximise under-represented groups, the innovative use of paint colour swatches so participants could identify the colours of ‘heroin’ which they had encountered, and the process of data analysis.

The paper draws on range of data sources, in the form of audio recorded semi-structured interviews, filmed ethnographic observation of participants during drug preparation and injection, and written fieldnotes.

The results reported tie in with the unknown research questions raised in the introduction – regarding the change in heroin and the desire to obtain the perspectives of people using fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted heroin. The benefit of the range of data sources is demonstrated in the results, as the authors present detailed data regarding opiate users’ perceptions of different types of heroin and their motivations for use (or not). The observation data are drawn upon to offer detail and context beyond the interview data. For example, the colour photographs presented in the results accompany the description of the proposed typology of new ‘heroin’ and show the reader the different colours of ‘heroin’.

Numerous quotations from participants are included to highlight the findings, although it is unclear if the names used to label the quotations are pseudonyms or their real names. We liked how some of the quotations include the interviewer questions, to show how the interviewers probed participant responses. Group members also thought that presenting the length of heroin use in the quotation labels provides useful contextual information.

The discussion reminds the reader of the main findings and centres on what the implications of the findings are for public health policy and practice. Specifically, the discussion considers how the use of fentanyl-substituted and fentanyl adulterated heroin may require ongoing consideration through a variety of strategies to minimise risk to users, including wider provision of naloxone, increased point of use drug testing, and the benefits of supervised injection facilities. Linking back to the exploratory nature of the study, the authors also suggest areas for future research – including validation of the heroin typology. The strengths and limitations of the qualitative approach are raised towards the end of the discussion.

Dr Charlotte Tompkins, Addictions Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London. charlotte.tompkins@kcl.ac.uk

You may also like…..

Harris, K.J., Jerome, N.W. & Fawcett, S.B. (1997) Rapid Assessment Procedures: A Review and Critique. Human Organization, 56(3): 375-378

Maher, L. & Dertadian, G. (2017) Qualitative Research. Addiction, Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/add.13931. [Epub ahead of print]

Marshall, M.N. (1996) Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13: 522-525.

.

The opinions expressed in this commentary reflect the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official positions of the Society for the Study of Addiction.