Public health specialist Dr Dan Lewer writes for the SSA about whether the recent increase in drug-related deaths in the UK could be linked to an ageing cohort of people who use heroin. He considers factors such as the impact of long-term health conditions, the policy shift towards getting people in-and-out of treatment, and the trend towards poly-substance use.

It was Edinburgh in the late 1980s when we first met Mark Renton, a young person who used heroin. He was a fictional character in Irvine Welsh’s novel Trainspotting, but his story runs parallel to real life.

People who use heroin today in London, Liverpool and Glasgow tend to be five to ten years older than those in other areas

Many people who started using heroin in the 1980s and 1990s continued using drugs and still do. They would now be in their 50s and 60s. This generation is the reason why the population of people who use heroin in different parts of the UK are getting older – a phenomenon often referred to as the ‘ageing cohort’.

A wave of heroin use in the 1980s and 1990s

Relatively large numbers of young people started injecting heroin in Glasgow, London, and Liverpool in the 1980s. The following decade the numbers of new people starting to use heroin decreased in these cities, but the wave spread to other parts of the country, and larger numbers started to inject in the North East, Yorkshire, the Midlands, and the South of England.

After the turn of the millennium, there were few people injecting for the first time in all parts of the country; the wave seemed to have passed. But many of those who started in the 1980s and 1990s continued using drugs. As a result, people who use heroin today in London, Liverpool and Glasgow tend to be five to ten years older than those in other areas.

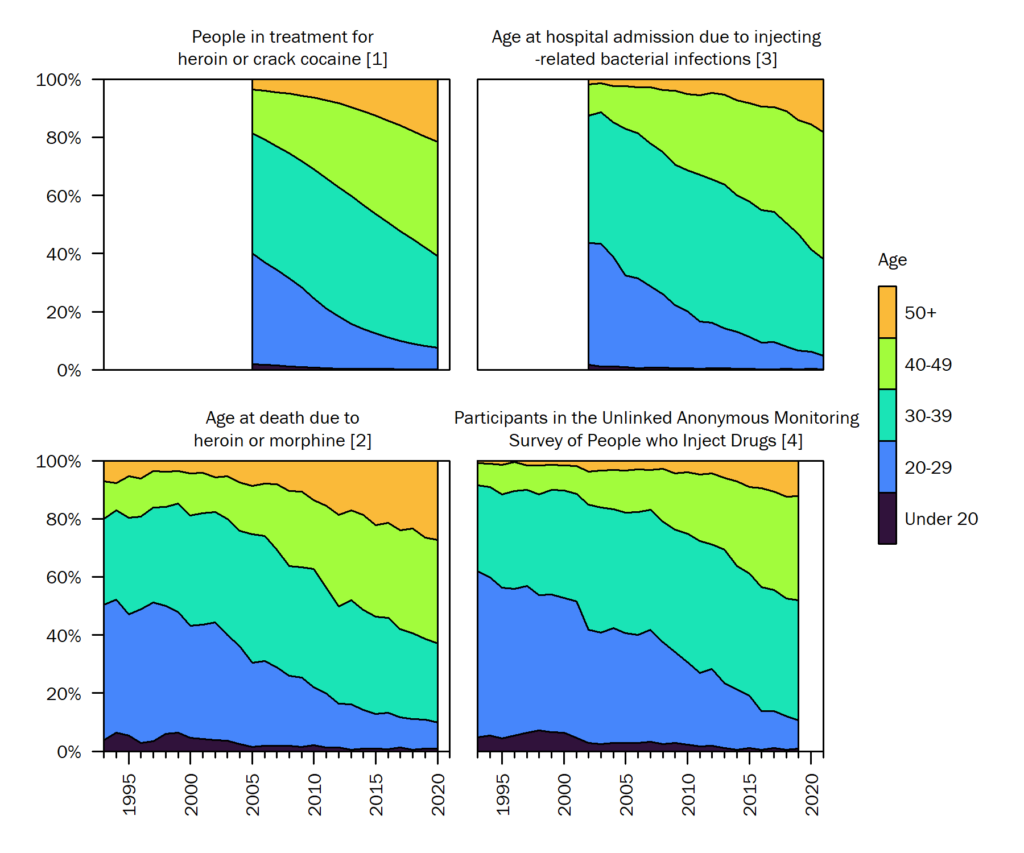

The idea of the ageing cohort is corroborated by data from drug treatment services, death certificates for people who died after using heroin, the age of patients admitted to hospital with abscesses at injecting sites and related infections, and surveys of people who inject drugs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: In the 1990s, people who used heroin in England were mostly aged in their 20s, while today they are mostly in their 30s and 40s

[1] Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2021). [2] Office for National Statistics (2021). [3] Hospital Episode Statistics (unpublished analysis of the patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of cutaneous abscess, cellulitis, phlebitis or thrombophlebitis, osteomyelitis, or endocarditis; and a secondary diagnosis of opioid dependence). [4] Public Health England (2021).

So why did this wave of heroin use happen? Perhaps it’s something to do with the cultural and economic experiences of Generation X – those born in the 1960s and 1970s. A high rate of drug overdoses and suicides in Generation X has been evident since the early 1990s, and it is possible that growing up during the unemployment, inflation, and labour force upheaval of the 1970s and 1980s had lasting effects on mental health.

Or perhaps the wave of heroin use was related to the supply of heroin. A new supply from the Middle East in the 1980s made heroin more affordable and available, which might have led more people to try it.

Perhaps it’s a cyclical process where a wave of drug use happens every few decades. For instance, some have compared heroin use to infectious disease outbreaks in which the number of susceptible individuals increases until an outbreak occurs, and after the outbreak, there is a period of ‘herd immunity’ when social networks become saturated.

There are counterarguments for all these theories, of course, and we might never know why heroin use changes over time.

Some people were worried that austerity policies after the financial crash of 2008, youth unemployment, and a renewed supply of heroin after the drought of 2011 would lead to a new wave. But, there is no evidence (yet) of a new generation of younger people using heroin, and we have seen decreasing rates of drug-related deaths and injecting-related infections in younger age groups.

The crisis in drug-related deaths

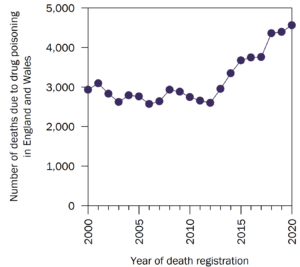

Against the background of an ageing cohort, is a crisis in drug-related deaths; the number of deaths caused by drug poisoning has increased every year since 2012 (see Figure 2). It seems obvious to link these two trends, and perhaps logical that the risk of overdose would be higher in a population in which the average duration of heroin use is 18 years and one-in-three has chronic lung disease. But let’s explore that link a bit more. Are older drug users actually at higher risk of a fatal overdose? Studies have mixed results on this question.

Figure 2: Drug-related deaths have increased every year in England and Wales since 2012 (Data source: Office for National Statistics, 2021)

Some studies suggest that people who use drugs and are in their 40s have a moderately higher risk than those in their 20s and 30s (1 2 3), while others suggest that the risk of fatal overdoses does not change as people get older (4 5). The relationship is probably complex, varying over time and by birth cohort, and might look different depending on how data are analysed. In any case, the risk of overdosing among people who use drugs clearly does not increase rapidly with age in the way that the risk of death due to heart disease or cancer does in the general population.

So, does the increase in drug-related deaths reflect the ageing of people who use drugs? Perhaps not. Drug-related deaths suddenly increased in 2012 after a decade of plateauing. In contrast, the age of people who use heroin has been increasing gradually over this whole period, and epidemiological studies (1 2) have found that the risk of fatal overdose within age groups has increased. For example, a 30-year old using heroin today has a much greater risk of a fatal overdose than a 30-year old using heroin in 2012.

This suggests that population ageing is probably not an important contributor to the increasing number of drug-related deaths. Instead, it looks like something happened in 2012 that caused the risk of fatal overdose to change suddenly. So what happened in 2012?

One inevitable consequence of an older population is that more have long-term health conditions

Firstly, there was a change in the national approach to treatment for opioid dependence. The National Treatment Agency (NTA), which was established in 2001 with a remit to increase access to methadone and other treatments for heroin dependence, was closed in 2013. Community drug treatment services became the responsibility of local public health teams, which often made deep financial cuts and replaced NHS providers with cheaper charitable providers.

The key performance metrics shifted from access-based indicators such as numbers-in-treatment (more is better) and retention (clients leaving treatment is bad), to recovery-based indicators such as ‘successful completions’ (the number of clients who leave treatment and report they are no longer using drugs). This reduction of funding and focus on discharging clients led to shorter and less stable periods of treatment, and staff having little time to engage with clients. Research shows that long-term and stable treatment is needed to keep people safe.

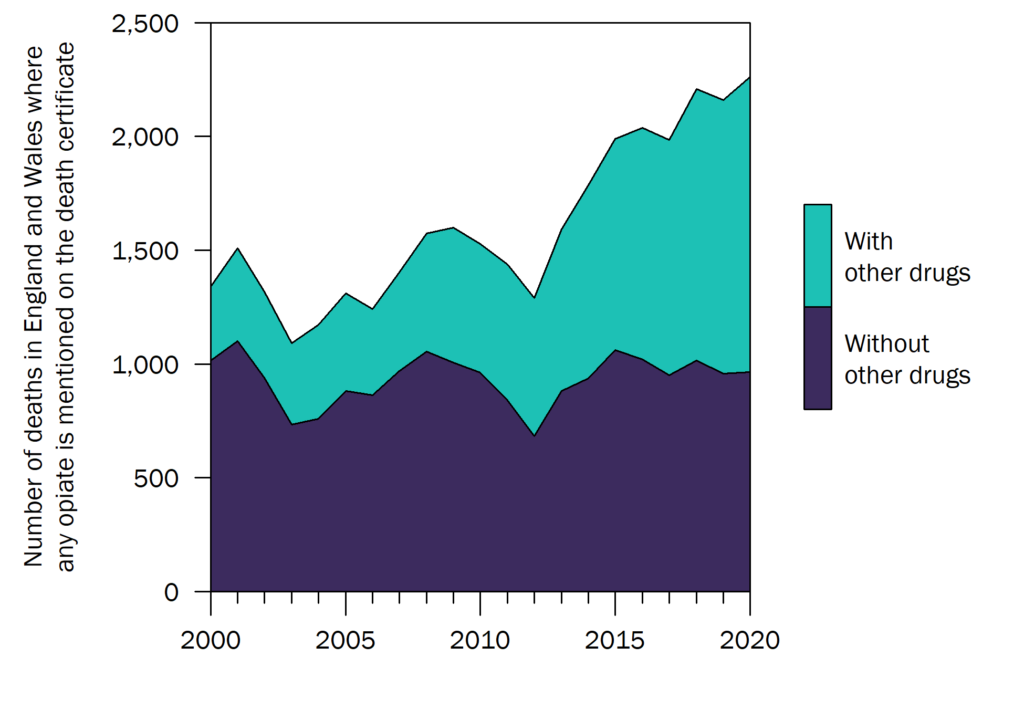

Secondly, there has been a big increase in poly-drug use (see Figure 3). More people are using different drugs at the same time. Sedative drugs used medically to treat pain and anxiety, such as benzodiazepines and gabapentinoids, are often used to enhance the effect of opiates and can have addictive properties. These drugs can interact dangerously with opiates to suppress breathing and increase the risk of death.

Figure 3: Poly-drug use has increased dramatically over the past 15 years and may be driving the crisis in drug-related deaths (Data source: Office for National Statistics, 2021)

In Scotland, which has the highest rate of drug-related deaths in Europe, three-quarters of deaths now involve a benzodiazepine and most are ‘street benzos’ – illicitly produced and unregulated drugs. Why poly-drug use increased in the past decade may lie in the heroin drought of 2011. Heroin was difficult to find, expensive, and low quality. People looked for alternative ways to get the same effect. Imagine if high-quality heroin was always available. Is it likely that we would have such a problem with ‘street benzos’?

These factors – the reduction in the protective effect of treatments such as methadone, and increase in poly-drug use due to a heroin drought ten years ago – appear to be the most likely explanations for the increase in drug-related deaths in the UK. So, rather than individuals being more vulnerable due to their age, it may be that the world has gotten risker – for which we may need to look closer at policies such as disinvestment in drug treatment services, and criminalisation causing an unsafe drug supply.

The growing importance of long-term conditions

The number of drug-related deaths is increasing, but this is not an inevitable consequence of people getting older. One inevitable consequence of an older population, however, is that more have long-term health conditions. Many of the cohort from the 1980s and 1990s smoke tobacco and have stressful lives. Among people who use heroin in England, the risk of death due to cancers, respiratory conditions, heart disease, or liver disease overtakes the risk of death due to drug overdose at age 42.

Services that support people who use drugs need a fundamental rethink based on the changing health needs of this ageing cohort. They need more clinically trained staff with general medical skills and they need to be better integrated with GPs and specialist health services. This costs money, but the alternative is an increasing burden of poorly-managed long-term conditions requiring frequent and expensive emergency care.

by Dan Lewer

Dr Dan Lewer is a public health specialist at University College London.

The opinions expressed in this post reflect the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official positions of the SSA.

The SSA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of the information in external sources or links and accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of such information.